Examining the Small Guard Crunch and the Value of Positional Size

Fewer small guards are receiving significant playing time in the NBA, and positional size is more valuable than ever. Maxwell examines the "Small Guard Crunch" and recent draft trends!

I spend a lot of time thinking about the important questions in life. Do we have free will? What happens after we die? How much sense does it make for an NBA front office to draft a small guard in a league that increasingly values positional size?

Small guards have come under fire recently. It’s a two-fold issue—positional size is king, and offenses are more sophisticated than ever before. For shorter players, it’s become harder to create openings on offense against longer, stronger opponents. Additionally, now that teams are more comfortable running their offense through whoever their best player is, the value of a more diminutive orchestrater has been diminished. If I’m running my offense through Nikola Jokic, a 6’4” sniper like Jamal Murray who can still make plays is a better complement than a passing maestro like Sharife Cooper who won’t space the floor as well and will be hunted on defense. Speaking of defense, it’s tough for the little guys there, too. Opponents hunt out size matches inside, and it’s simply harder for shorter players to cover as much ground as their taller peers in rotational settings.

As someone who spends a lot of time focused on the NBA Draft, this raises serious questions about how prospects should be evaluated. Earlier this cycle, our own Corey Tulaba wrote a fantastic piece examining how some of the smaller guard prospects in this class compare statistically to those who have stuck. Today, I’m going to do something slightly different. We’re going to get into the meat and potatoes of a few different questions:

What is the hit rate on guards 6’3” and under?

How does that hit rate on those players fare relative to other sizes, and why?

What are the differences between the small guards who were hits and the small guards who were whiffs?

How will this experiment inform my draft philosophy going forward?

The Rules and The Data Sample

Let’s take a look at how I determined my categories for this exercise!

-I examined players selected in the last five drafts. The idea here is to get a decent sample, but still keep it “modern” enough to be relevant to where the league is headed. Keep in mind, this does trim out a talented small guard crop in 2018 (Trae Young, Jalen Brunson). But the reason I went more recent is because this is an incredibly recent phenomenon, as the data will show. The “small guard crunch” popped up in fast and dramatic fashion. I wanted to account for that first and foremost. This is more about where the league is going rather than where it has been. Also, I have a desk job, a wife, and a child, I’ve got to draw the line somewhere.

-All listed heights are based on BartTorvik listed height during the player’s pre-draft season. For non-college players, I used Wikipedia. If a player was listed over 6’4” during their pre-draft season, I moved them to that group. For example, Isaiah Wong was listed at 6’3”, but then magically levelled up to 6’4” as a senior, so I didn’t include him in the small guard group.

-Players are categorized into three groups. “Hits,” “whiffs,” and “in-betweens.”

-Hits are in bold. A hit is defined as a player who registered over 20 MPG for the team that drafted them. They also weren’t a clear negative during those minutes.

-I ran into what I’ll call, “Rebuilding Minutes Grifters,” or guys who got 20 MPG out of the gate but are far from being good by NBA standards. In extreme cases, some of these players ended up washing out of the league (Jarrett Culver in his height category). In those cases, I’m not counting that player as a “hit.”

-Whiffs are in italics. Players who have registered zero NBA minutes this season are classified as “whiffs.”

-The in-between group met neither the “hit” or “whiff” criteria. Some of them are solid NBA players who found their footing with another organization, others are hanging on by a thread. “Too early to tell” players ended up in this category. This is also where I put players in the most recent class who are getting minutes but haven’t been close to positive players yet (Scoot Henderson).

-I had to use my discretion when it came to players who received minutes early, but now appear to be far from positive NBA players, such as Kessler Edwards. In those instances, I didn’t classify those players as “hits” or “whiffs,” so they are in the “in-between.”

-I defaulted to an “in-between” grade on “draft and stash” players from the 2022 and 2023 classes.

2019:

-Ja Morant, 2nd, 6’3”

-Darius Garland, 6th, 6’2”

-Carsen Edwards, 33rd, 6’1”

-Tremont Waters, 51st, 5’11”

-Justin Wright-Foreman, 53rd, 6’2”

-Kyle Guy, 55th, 6’2”

-Jaylen Hands, 56th, 6’3”

-Jordan Bone, 58th, 6’3”

2020:

-Kira Lewis, 13th, 6’3”

-Cole Anthony, 15th, 6’3”

-Tyrese Maxey, 21st, 6’3”

-Immanuel Quickley, 25th, 6’3”

-Payton Pritchard, 26th, 6’2”

-Malachi Flynn, 29th, 6’1”

-Tyrell Terry, 31st, 6’1”

-Saben Lee, 38th, 6’2”

-Tre Jones, 41st, 6’3”

-Yam Madar, 47th, 6’3”

-Nico Mannion, 48th, 6’3”

-Cassius Winston, 53rd, 6’1”

-Grant Riller, 56th, 6’3”

2021:

-Davion Mitchell, 9th, 6’2”

-Bones Hyland, 26th, 6’3”

-Miles McBride, 36th, 6’2”

-Jared Butler, 40th, 6’3”

-Sharife Cooper, 48th, 6’1”

-Marcus Zegarowski, 49th, 6’2”

2022:

-TyTy Washington, 29th, 6’3”

-Jaden Hardy, 37th, 6’3”

-Kennedy Chandler, 38th, 6’0”

-JD Davison, 54th, 6’3”

2023:

-Scoot Henderson, 3rd, 6’3”

-Marcus Sasser, 25th, 6’2”

Question One: What is the hit rate on guards 6’3” and under?

In the last five drafts, 33 selected players met the 6’3” and under criteria. Of that list, three players (9.1%) have made an All-Star team (Ja Morant, Darius Garland, and Tyrese Maxey). Eight players (24.2%) have gone on to play over 20 MPG for the team that drafted them and contributed in at least a neutral way. Players like Miles McBride, Scoot Henderson, and Marcus Sasser could add their names to that list in time. Bones Hyland was also extremely close (19.5 MPG), so it’s tough to call him a miss. Still, to stay consistent, they remain in the “in-between” category. Conversely, 14 of the 33 (42.4%) have yet to play a single minute of NBA basketball during the 2023-2024 season.

What’s more, the hit rate gets worse the more you lower the height. Of the eight who met the 20 MPG threshold, five were 6’3”, and the other three were 6’2”. If we change the definition of a “small guard” to 6’2” and under, we’re left with 16 players. That gives those players a 18.8% hit rate, with the caveat that McBride and Sasser could up the average. Of the 6’1” and under crowd, Malachi Flynn is the only guy kicking around the NBA in any capacity.

Question Two: How does that hit rate on those players fare relative to other sizes, and why?

Let’s take a look at our small guard group as opposed to other height groupings.

Players 6’3” and under:

Players: 33

All-Stars: 3 (9.1%)

Hits: 8 (24.2%)

Whiffs: 14 (42.4%)

Players 6’4” - 6’6”:

Players: 97

All-Stars: 3 (3.1%)

Hits: 34 (35.1%)

Whiffs: 24 (24.7%)

Players 6’7” - 6’9”

Players: 94

All-Stars: 2 (2.1%)

Hits: 35 (37.2%)

Whiffs: 12 (12.8%)

Players 6’10”+

Players: 53

All-Stars: 1 (1.8%)

Hits: 13 (24.5%)

Whiffs: 12 (22.6%)

Findings and Notes:

1. Small guards have the lowest “hit” rate, and if you look around the league, it’s easy to understand why. This season 223 players have appeared in 20+ games and averaged over 20 MPG. Only 28 of those players, or 12.6%, stand 6’3” and under. Drop that height to 6’2”, and you’re left with 16 players, or 7.2% of all 20 MPG contributors. There simply aren’t a lot of short dudes getting big minutes. When teams draft small players, they are attempting to thread a narrow needle.

2. Small guards have the highest “whiff” rate of any group, and by quite a substantial margin. When these guys don’t stick, they are out of the league fast. NBA teams will continue to kick the tires on players in the 6’7” - 6’9” range even if they aren’t a hit. Guys who play a significant number of minutes simply tend to be bigger.

3. This presents a two-fold dilemma when drafting a small guard. First off, you’re shooting for a tougher probability. That’s not to say that small guards can’t bring significant value. This group has the highest All-Star rate, after all! Ja Morant is an All-NBA talent. Darius Garland is awesome. In hindsight, getting a player of Tyrese Maxey’s caliber with the 21st pick was highway robbery. Small guards can hit in a big way, and it’s foolish to ignore that. But while small guards can still alter the trajectory of a franchise, there is a much harsher floor beneath their feet. The downside is brutal. When a small guard doesn’t work out, few teams are eyeing them for a reclamation project. The margins are razor-thin.

4. This is why taller players have an easier time avoiding whiff status. A player like Admiral Schofield avoided inclusion on the whiff list while Kennedy Chandler didn’t. The Orlando Magic see the potential value in Schofield, a 6’5”, powerfully built wing who has put together some strong shooting seasons in college and the G League. Things haven’t materialized for him on the NBA level, but even at 26 years old, the Magic have kept him in their organization and keep trotting him out there. If the shot does start to fall, he’ll fill a significant need for them. They need shooting, and if they can get it from a guy with his frame, that’s a big win on the margins. It would be much more difficult to acquire a 6’5”, physically strong sharpshooter than a small guard who is having a nice G League season, which is what Kennedy Chandler is at this point.

5. It is difficult to recoup value on a small guard whiff. Chandler has played 0 NBA minutes this season despite being a good player in the G League. Teams simply aren’t going out of their way to foster the development of those types of players because they’re far less likely to turn into 20+ MPG guys. This is probably why the Grizzlies, who drafted Chandler, released him instead of trading him. I’m sure they would have loved to trade him for something, but they didn’t, and I’m assuming it’s because they couldn’t find anything worthwhile in return. As I said earlier, this is a recent phenomenon, and it’s evident in the sharp decline of small guards taken after the 2020 draft. Teams would rather hope to get “found money” with a guy like Craig Porter as an undrafted free agent as opposed to expending their draft capital on what likely amounts to a high-risk, low-reward swing in the second round.

6. The 6’4” - 6’6” group was an interesting mixed bag. One trend stood out—the danger of the “NQW.” NQW, or Not Quite Wing, is a phrase I stole from friend of the site Chuck (and if you aren’t a Chucking Darts listener, you are a loser). The NQW often doesn’t have the size to guard up the lineup on defense, and they also don’t have enough guard skill to comfortably play down it on offense. This limits who they can guard on defense and how effective they can be on offense. In many cases, it’s easier to simply send a taller player out there.

While they may not always meet “whiff” criteria, there were a significant number of clear non-hits for teams who drafted certain NQWs. James Bouknight, Keon Johnson, Jaden Springer, Josh Christopher, Blake Wesley, Wendell Moore, Trevor Keels, *the deepest sigh imaginable* Johnny Davis…I could go on. But the bottom line is, there were a lot of guys who fit this mold coming out of college, and the value return for the drafting team has been minimal. If a guy doesn’t have true wing size, you don’t want them running your offense, and/or shooting questions exist, you may want to stay away.

7. Players in the 6’7” to 6’9” range have produced the best hit rate in recent years. This further demonstrates the idea that positional size is king. Even when a player in this height range isn’t a clear hit right away, their sheer size gives them a better runway to become one. Let’s take a look at two guys who I believe demonstrate this phenomenon well—Deni Avdija and Trevor Keels.

Avdija entered the league with a good framework. He was 6’9”, he had some playmaking chops, he rebounded, and he was a good defender. Unfortunately, there were questions about if he could be a reliable shooter. In his final pre-draft season with Maccabi Tel-Aviv, he hit 33% of his threes, but he was a dismal 58.8% at the charity stripe. His first few seasons were okay, but inconsistency as an outside shooter prevented him being viewed as Actually Good. At 31% from deep on lower volume, it was tough to keep opposing defenses honest when he was on the floor. This year, he’s knocked down 39.9% of his threes. Now, the four-year, $55 million contract extension he signed back in October is a giant bargain. Every NBA team could use a 6’9” guy who does a little bit of everything.

Trevor Keels came out of Duke as a highly touted one-and-done. At 6’4”, Keels was a fantastic defender with some playmaking juice to him. Similar to Avdija, Keels wasn’t a good shooter. He went 31.2% from deep and 67% at the free throw line during his single college season. While Avdija was the 9th pick in his class, Keels slid to the 42nd pick in class before he was taken by the Knicks, who sent him to the G League on a two-way contract. After shooting 32.2% from deep in his first G League season, the Knicks cut bait on Keels and waived him.

8. Bigger players are more likely to receive patience and developmental attention than their smaller peers. It made sense for the Wizards to be patient—a 6’9” guy who can do a lot of stuff won’t totally kill your team, even if the jumper isn’t at a league-average level. The same can’t be said for someone who is 6’4”. The taller guy is probably a better rebound and screener, and he can probably guard more positions effectively. He’s easier to put in the dunker spot or to use as a roll man. Size is why Trevor Keels went later than Deni Avdija in their respective draft classes, it’s why Deni Avdija got continued developmental opportunities to work through his shooting issues, and it’s why the Knicks let Keels go for nothing.

If Trevor Keels was 6’9”, it’s hard to imagine him falling that far on draft night and a team giving up on him so quickly. But it’s harder for smaller players to get close to net neutral if they can’t shoot. Players like Keels and Kennedy Chandler haven’t seen an NBA floor this season. Conversely, the Pacers just converted Kendall Brown to a standard contract even though he hasn’t proven anything on an NBA court just yet. It doesn’t mean that he can’t, or won’t, but this further points to taller players getting more time to see things through.

9. The value of, “he won’t get you killed out there” plays a part in why the whiff rate on guys in the 6’7” to 6’9” role is so low.

Taller players don’t just get better opportunities, they get more of them, too. The Blazers moved on from Trendon Watford this past offseason, and the Nets scooped him right up. He doesn’t have the biggest or most consistent role, but simply being that size and having good feel for the game goes a long way. Dalano Banton is on his third team, but being tall and savvy has kept his foot in the door. Plus, the allure of one of these guys turning the corner the way Avdija did is enticing, even if it’s an unlikely outcome. At this stage, Grant Riller’s best-case scenario still probably doesn’t end up with him getting 20 minutes a night. Conversely, Trendon Watford is a jump shot away from that.

10. The 6’10”+ group had a similarly low hit rate to the small guard group. Is the NBA going to move away from its tallest players? I’d confidently say no. It appears as if we simply had a fluky run of…how do I say this nicely…suboptimal tall guy drafts. Let’s take a look at how the 2020 class panned out, for example:

James Wiseman, 2nd

Jalen Smith, 10th

Aleksej Pokuševski, 17th

Zeke Nnaji, 22nd

Udoka Azubuike, 27th

Vernon Carey, 32nd

Daniel Oturu, 33rd

Nick Richards, 42nd

Marko Simonović, 44th

Reggie Perry, 57th

James Wiseman has struggled mightily. Jalen Smith has found his footing in Indiana, but only after Phoenix was proactively taking steps to kick him to the curb. The Poku experiment didn’t go how we all hoped. Zeke Nnaji has been a mixed bag. Udoka Azubuike has battled health and skill issues. Vernon Carey, Daniel Oturu, Marko Simonovic, and Reggie Perry are all gone. The player who likely provided the best value to their drafting team as an actual player on the basketball court here is Nick Richards.

The class before that was rough, too. Jaxson Hayes and Nic Claxton met the “hit” threshold. Daniel Gafford found his footing after the Bulls traded him, and Goga Bitadze has become a positive contributor in Orlando after things didn’t click for him in Indiana. Again, because bigger guys get more chances and find an easier time staying above water, the whiff rate here is lower, too. But players like Bruno Fernando, Luka Šamanić, and Mfiondu Kabengele didn’t help the hit rate despite being Top 40 picks.

But back to the original question—I think this turns around in the next few seasons, and I don’t think the tallest players are going anywhere. There has been recent influx of tall guy talent. In the last two drafts, we’ve added Paolo Banchero, Chet Holmgren, Jabari Smith Jr., Walker Kessler, and Victor Wembanyama to the league, just to name a few. Those dudes are going to be around for a long time, and they aren’t the same type of mismatch targets that their small guard counterparts can be in a playoff series.

11. If you want to be a dreamer for the small guards, this is what you can point to as a glimmer of hope. Maybe we’ve just happened to run into a few bad small guard classes, and something better is ahead of us. Still, I’m skeptical of that. As teams continue to build around whoever their most talented player is, there will be limitations in utilizing smaller players as complementary pieces on both ends of the floor. That said, there’s still a chance that the small guard may not be as dead as some believe.

Question Three: What are the differences between the small guard who were hits and the small guard who were whiffs?

I broke this down into a few different categories. Let’s start with the category elegantly named, “Body Stuff,” as it’s where we see some legitimate divergences.

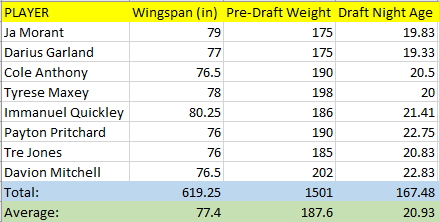

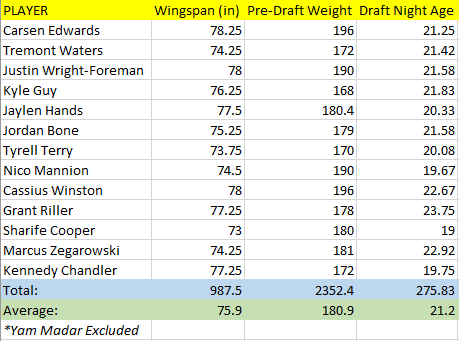

Body Stuff:

On average, the small guards who have stuck have an extra inch and a half of wingspan and an extra 6.7 pounds of body weight. That may not seem like a lot, but the NBA is a game of inches and ounces. On a basketball court, it’s a big difference. The fact that none of the successful small guards had a sub-6’4” wingspan stuck out like a sore thumb, especially given that it was the average mark for the whiff group. Obviously, there are exceptions to these findings. Carsen Edwards, Justin Wright-Foreman, and Cassius Winston had plenty of length and bulk, but they didn’t pan out. Conversely, Ja Morant and Darius Garland entered the association as some of the lightest players in the league.

What Morant and Garland did have, though, were outlier talents. Morant was an exceptional vertical athlete with a high level of feel. Garland has out-of-this-world touch and range as a scorer. Going back further, Trae Young overcame the skinniness hurdle by exhibiting phenomenal shooting ability and wonderful timing as a passer. Even longer ago, Chris Paul got over the hump with ease thanks to his playmaking wizardry, dogged defense, and off-the-catch shooting. There have always been small guards who were skinny that broke through, and typically, it’s been because they had something that made them truly special. If a guard is short and thin, it’s a “stay away” for me unless there’s a big, meaningful hook skill-wise.

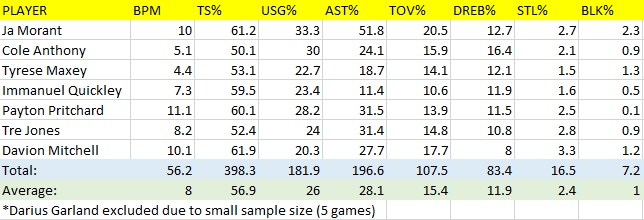

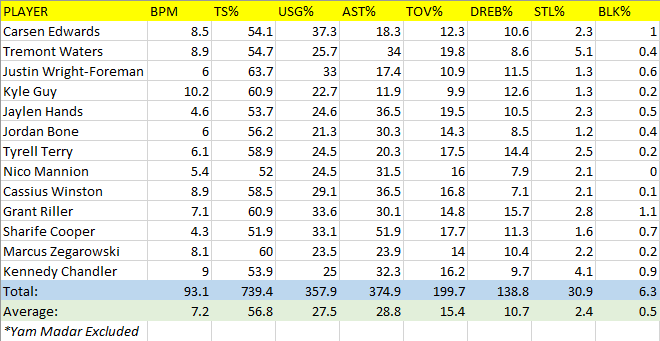

Advanced Statistics:

The next thing I looked at was some general advanced numbers from players during their final pre-draft college seasons. This was pretty interesting to me because, as we’ll see in the next section as well, the players in the hit group weren’t as similar to one another as you might expect. Their usage and assists rates were up and down. Some were complete pests on defense while others weren’t. Some posted gaudy BPMs, some didn’t. This begins to make it evident that “spreadsheet scouting” can only take you so far when it comes to this player type. While neither category is a slam dunk, “this guy is going to stink” metric, lower block and rebounding rates were more common in the whiff group, as were lower BPMs.

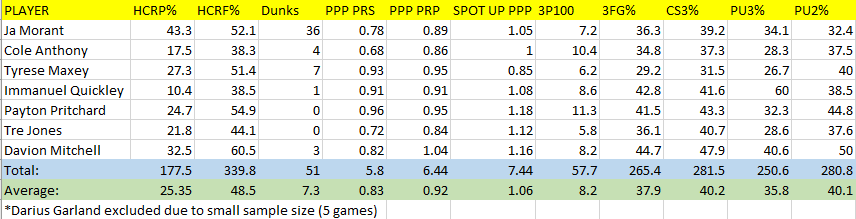

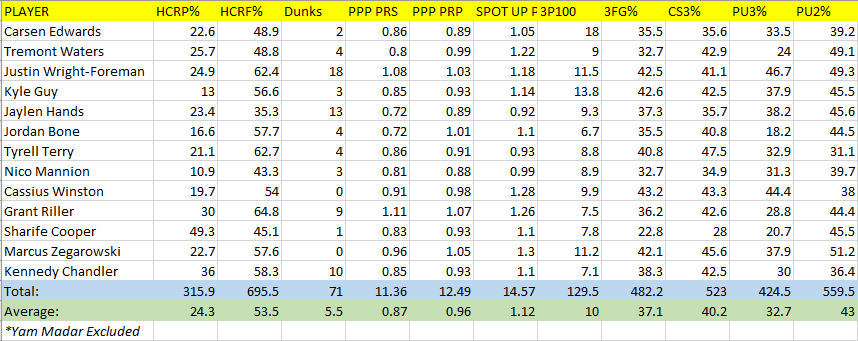

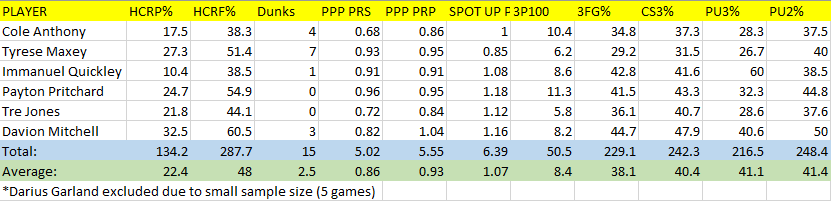

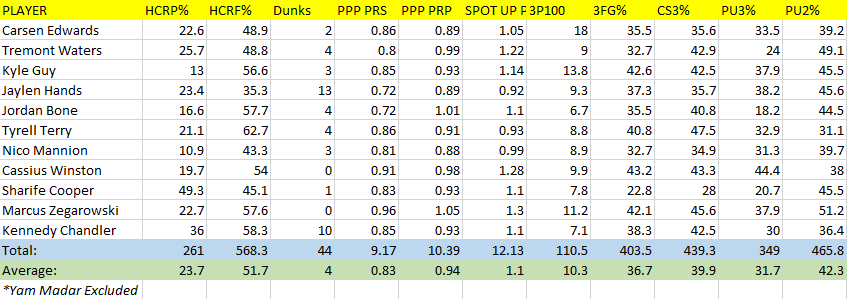

Shot and Play Type Efficiency:

Next, I wanted to take a look into the Synergy numbers, particularly as it pertains to shot diet and overall efficiency. Here are the stats I looked at, and how I abbreviated them in the tables below:

-HCRP%, or Half Court Rim Pressure Percentage. This is what percentage of a player’s shots in the half court came at the rim.

-HCRF%, or Half Court Rim Finishing Percentage. This is the percentage a player shoots on their field goal attempts at the rim in the halfcourt.

-Dunks, like when a player does a sick dunk.

-PPP PRS, or Points Per Possession as a Pick-and-Roll Scorer.

-PPP PRP, or Points Per Possession on Pick-and-Roll Possessions including Passes.

-SPOT UP PPP, or Points Per Possession on Spot Up possessions.

-3P100, or number of three-point field goals attempted per 100 possessions.

-3FG%, or three-point field goal percentage. Come on, everyone knows that one!

-CS3%, or percentage on catch-and-shoot three-point attempts.

-PU3%, or percentage on pull-up three-point attempts.

-PU2%, or percentage on pull-up two-point attempts.

One of the first things that jumped out to me was how relatively unimportant the dunk number ended up being. Dunks have long been used as an athletic indicator, and I think that’s still a solid line of thinking. However, with small guards, it doesn’t seem to indicate much in terms of NBA success. Those numbers are all over the place, and two zero-dunk guys managed to stick.

The next thing was that…wow, on paper, these players aren’t so different after all. I wondered if the fact that Justin-Wright Foreman and Grant Riller did their work in a mid-major conference was the reason the whiff group stacked up so well. So, I pulled them, as well as Ja Morant from the hits group, to see if that changed anything.

Shot and Play Type Efficiency Mid-Major Exclusion:

Well, not really! You could say pull-up three-point shooting is the key difference, but even then, I’m not so sure. Immanuel Quickley’s low volume efficiency is the only reason the hit group is above water at all! The hit group got to the rim less, finished worse there, and shot fewer threes, but made a few more of them.

Trying to seek out trends here has been maddening. Did players who liked to launch threes but struggled to finish fail? Yes, but that describes Immanuel Quickley and Cole Anthony, too. There were some extremely poor pull-up three-point shooters in the whiff group, but Tyrese Maxey and Tre Jones weren’t lighting the world on fire on that front either. Maxey had strong shooting priors during his prep career, but Jones was never special in that respect.

In my opinion, four different things are going on here:

1. We are dealing with extremely small samples. A 14-player whiff group and a seven-player hit group? That’s tough to work off of and draw any hard, fast conclusions from. Sometimes, patterns can emerge even in a smaller data set, but I don’t even see anything too meaningful from the statistical portion, outside of block rate being a solid indicator. Don’t tell my wife this, she’s going to kill me if she finds out I did this much work and basically concluded a section with, “OH WELL!”

2. Stylistic diversity makes things even tougher to pin down within a small sample. Even just looking at the hit group, these are very different types of players. A Tyrese Maxey style secondary initiator is different than a Ja Morant lead guard, and that’s different than a defensive table setter like a Tre Jones.

3. The NBA game is a matter of inches and ounces. Again, physical dimensions were where we saw the most pronounced differences. I’d also estimate that the hit group is more athletic, generally speaking, than the lower group. Kyle Guy and Immanuel Quickley had similar shot diets and advanced numbers, but Quickley’s, well, quickness, differentiates him in an eye test setting. His massive wingspan advantage doesn’t hurt, either. They’re in different worlds defensively, which is hard to account for on a statistical basis.

4. Length, weight, strength, and ability to gauge athleticism are key when evaluating these types of players, as statistical spreadsheets can make them appear more similar than they actually are on a court. At the college level, Marcus Zegarowski was a more efficient finisher than Tyrese Maxey. But Maxey’s world class first step and ability to absorb contact had him more suited to an NBA floor than Zegarowski. Zegarowski was stubbier than Maxey and 17 pounds lighter. He was slower, too. When Zegarowski got the G League, he struggled at the rim, and that’s part of why he never made it onto an NBA floor. You have to watch the games, and you can’t totally hand wave physical concerns.

Question Four: How will this experiment inform my draft philosophy going forward?

I’ve become increasingly averse to what I’ll dub, “non-special smaller guards,” and that dovetails with what we are currently seeing across front offices. This further affirmed that for me. Draft capital is precious. The ethics of the process can be discussed another time on another day, but the draft is the rare time that a front office has a captive player pool. The data suggests that smaller players are more likely to be out of the league quickly, especially when they’re on the slender side. People can hand waive at the combine process, but length and weight matter significantly on the lower end of the spectrum. Measurements need to be taken into account. Additionally, there needs to be an understanding that when drafting this type of player, it can go wrong in a hurry, and it will be hard to find a second team wanting to give up something of value when it’s time to move on.

That said, the baby shouldn’t be thrown out with the bath water when it comes to small guards. Statistically, it may be riskier to target a smaller guard, but they’ve also produced a great All-Star rate. The goal of an NBA team is supposed to be winning games. Ja Morant, Darius Garland, and Tyrese Maxey help their teams do that. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have received All-Star nods. It’s important to have a draft philosophy, but it’s also important to avoid setting foolish exclusions on an entire height category when it may provide significant value.

I also came out of this exercise with a newfound concern about the pitfalls of the NQW. There have been successful players in this architype—Eric Gordon, Buddy Hield, and Desmond Bane (due to his shorter wingspan) come to mind. Being cut from this cloth far from guarantees disaster. I’m sure a lot of front offices would love to have gone back in time and drafted Desmond Bane earlier. But next to small guards and bigs who just weren’t very good, this was one of the groups that I saw running into NBA trouble most often.

This process also reinforced how valuable players in that 6’7” to 6’9” range can be. When there’s a baseline level of skills on both ends with one genuinely positive trait (shooting for Corey Kispert, defensive playmaking for Tari Eason, etc.), that’s typically enough to get them on the floor. From there, they can round out their issues through meaningful NBA reps. I think a big part of the, “you should draft bigger” draft philosophy tends to spawn from the idea that generally speaking, wing-sized guys are harder to mismatch in a playoff series. But in a league where all rookies tend to be less than efficient, simply being larger makes it easier to stay on the floor during the regular season. That matters. You have to play in the regular season before you’ll ever get playoff minutes. If there’s a player in the 6’7” to 6’9” range that you think can get on the floor immediately, it’s about as safe of a pick as you can make. At worst, you’re getting someone who can hang, and at best, you’re getting a playoff contributor.

On the big man front, I didn’t necessarily learn anything new, but there were some good reminders. Typically, the centers that are sticking are either great defenders pre-draft (Walker Kessler, Dereck Lively), supremely skilled (Santi Aldama, Alperen Sengun), or both (Chet Holmgren, Evan Mobley). If someone isn’t checking one of those boxes, you can expect a more modest outcome. There haven’t been any major “project” success stories out of this group. Athletic tools are awesome, and they’re common among those that pan out, but if you’re coming into the league without a real level of skill competence, it’s going to be a very uphill battle.

Conclusion

Well, I think that about does it. I hope you learned something today. This has been one of the most exhausting features I’ve put together, so I hope you enjoyed it. I couldn’t be more grateful for this platform here at No Ceilings, and it means the world to me that you stuck with this column long enough to get here. Make sure you’re subscribed to our Substack for more daily content. Also, follow me on Twitter/X! Now, let’s get to some Quick Hits!

Quick Hits

-Check out this 25-second stretch from Alex Sarr:

First, he gets into position as a help defender to prevent an easy look at the rim. Then, he covers ground to close out in the corner. After that, he gets switched onto a smaller player and swats his shot. In 25 seconds, he showed a lot of critical modern defensive abilities. On the other end, he can put the ball on the deck, pass it, and he’s an advanced shooter for his age and size. Remember, the bigs that are clicking can defend, have supreme skill, or both. Alex Sarr has both. He’s still the number one player on my personal board.

-Go check out my interview with Jaylen Wells right here! The 6’8” junior has been one of college basketball’s best surprise stories this season. A D-2 transfer up, Wells has posted 15.8 PPG on 47.0/43.8/84 splits since moving into Washington State’s starting lineup in mid-January. He’s also posted 1.3 APG to 0.5 TOV during that stretch, demonstrating his reliability as a decision-maker. Wells takes nearly 10 threes per 100 possessions, and he’s showcased a high level of efficiency while doing that in his first D-1 season at a Power Five school. Still, if teams chase him off the line, he has a counter game and mid-range shot-making bag. Hey, anyone read any good articles lately about the value of taller players with a skill that can get them on the floor right away? Given the Jaylen Wells tape a look if you haven’t already and listen to our interview!

-Pelle Larsson’s game against Oregon last week was what I want to see from him every time he’s on the floor. The 6’5” senior’s strength goes a long way on defense, where he handles taller players with much more ease than one might expect. He can also stick to guys like glue off the ball when he needs to. Opponents respect his shot, which opens up his driving game. His power and touch make him a fantastic finisher (61.8% at the rim in the halfcourt), and his passing is tremendous. Still, despite Larsson being a 43% shooter from deep on the year, he only takes 4.8 triples per 100 possessions. His motion is elongated, which is why he often ends up going the pump fake and drive route as opposed to shooting over a closeout. The Larsson that launched six threes against Oregon? That’s the one I want, and that’s the one who I think could carve out an NBA roster spot.

-Minnesota’s Cam Christie has started to gain some traction late in the season. It’s easy to understand why—he’s a 6’6” freshman who is draining 41% of his threes on high volume. What’s more, he’s a versatile shooter who can spot up, knock down transition triples, and pull up from behind the arc while running a ball screen. He’s got some playmaking chops as both a creator and connector, too. I’d still like to see him take another year with the Golden Gophers before entering the NBA, though. He doesn’t get to the rim much, and he’s not good when he gets there (37% in the halfcourt, per Synergy). Part of it is strength through contact, part of it is process-oriented, as he’s too content to go straight into heavy traffic and settle for tough looks. Additionally, it would be nice to see him take a step forward on defense, where he’s been fairly uninspiring. That said, Christie isn’t a slouch athletically or from a frame standpoint. He could really surge with the right improvements, and I’d feel best about him workshopping those skills against college players rather than jumping into the deep end of the pool first. If he goes back, he’d be at the top of my sophomore breakout list.

-Keep an eye out for South Florida’s Kasean Pryor. The 6’9” junior is extremely comfortable putting the ball on the deck for a player his size. He gets low to drive, and he’s fluid when he needs to counter or change directions. His passing vision is pretty solid, too. While he’s only a 32.5% three-point shooter, Pryor is an 82.4% free throw shooter, and his stroke looks natural. On defense, he has no problem sliding his feet with smaller guys, and he’s a big-time elevator to swat shots around the basket. He hasn’t gotten a lot of buzz yet, but a 6’9” dude with defensive versatility who has posted 14.7 PPG on 44.8/40.4/86.6 splits over his last 15 games should be on your radar.

-A sleeper to monitor who will be in this year’s draft is Riley Minix. The 6’7” grad from Morehead State built up some buzz in NBA circles after a 19-point outing against Alabama and an 18-point showing against Purdue. Minix didn’t shoot well from three in that game, but his career mark of 40.8% from deep at Southeastern University in his four prior seasons gave room for optimism. In Ohio Valley Conference play, Minix knocked down 37.6% of his triples on good volume. He occasionally shoots a moonball, but he’s comfortable moving into his jumper, and he gets it off quickly. Physically, the dude is a powerhouse. He’s strong, tough to knock off his spot on drives, and he has the explosiveness to finish above the rim. Defensively, he’s an intelligent off-ball player. His tags are on point and he knows where to be as the low man. Positionally, he’s sort of an odd 3/4 tweener. Offensively, he likes to operate out of the mid-post a lot, so that will be an adjustment at the next level. I also worry about his foot speed guarding on the perimeter, as he often crosses his feet when tested laterally. Still, given what Minix has done in his first D-1 season, his shooting, power, and feel, don’t be surprised if his stock starts to soar over the next few months.

-You know who fits the “strong and long” guard threshold? South Carolina’s Ta’Lon Cooper. The 6’4” graduate is sturdy and has no issue guarding up the lineup. He’s always been a solid defensive playmaker, but the fundamentals are great, too. He did an awesome job of stifling Dalton Knecht for stretches in their match-up against Tennessee. His ability to navigate screens on defense, both on and off the ball, stands out every time I see him. Cooper’s over three-to-one assist-to-turnover ratio and 45.5% from deep with NBA range are also extremely valuable skills. At under 10 PPG, he’s probably not at the top of many radars, but I think he’s a sneaky E10 candidate given the number of boxes he checks.