Ranking the Top Basketball Leagues in the World

We look at hundreds of thousands of player moves over the past five years to try and answer the age-old question: What are the best basketball leagues in the world?

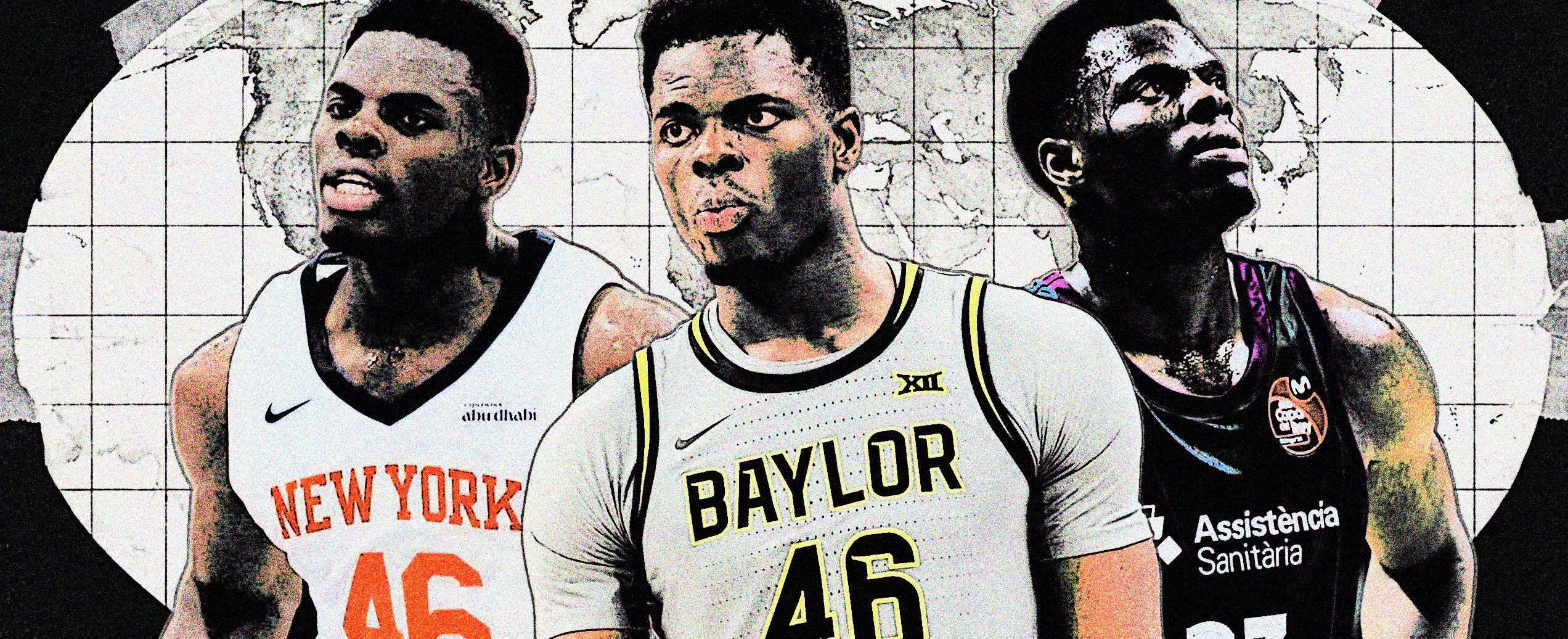

Over the past few weeks, James Nnaji has gone from an NBA draft-and-stash prospect to one of the most widely discussed international recruits of all time, as he became the first player drafted by an NBA team to suit up in the NCAA in over 45 years. His recent move to Baylor, however, is just the tip of the iceberg: according to information I compiled from RealGM, during this 2025-26 season, there have been 276 college players who made an appearance in at least one of 75 different international competitions the year prior.

With the origins of players coming into college basketball becoming increasingly diverse, it’s key for NCAA teams (and their decision-makers) to understand levels of competition around the world. There are thousands of domestic leagues, continental championships, national team tournaments, youth competitions, and special events. Ranking those levels of competition has been a titanic, if not nearly impossible, task.

What makes it so hard? Even when continental (and world) tournaments help funnel the best teams from a country or region into a single competition, teams from domestic leagues don’t always play teams from other domestic leagues. There are also teams that operate entirely within their own bubbles: national teams don’t play club teams (at least in official competitions), while U16, U18, and U20 teams don’t compete outside their age categories. That makes it nearly impossible to find a common opponent as a point of comparison, even after hundreds of degrees of separation.

Long story short: it’s hard to rank teams that don’t play against each other. Just ask the College Football Playoff committee.

While there’s no publicly available league ranking or translation model, there is one great tool: Layne Vashro’s article Measuring Level of Competition Around the World. In it, he came as close as anybody in the public space to finding that holy grail, creating an index that, in his own words, measures “what statistical production in each league says about NBA potential.”

There is, however, one problem with the article that has absolutely nothing to do with the (excellent) quality of the research: it was published in 2015. Since then, many of the competitions listed have ceased to exist, many new ones have emerged, and the global basketball landscape has changed significantly, its map redrawn by shifting economic realities across countries and the irruption of NIL, which has made college basketball a more attractive market for international players.

With Layne now working for an NBA team, I doubt we’ll ever see an update, so I set out to build my own ranking of basketball competitions.

I know how short attention spans are in 2026, so before getting into the hows and whys, I’ll get straight to the what.

If by any chance, the list is hard to visualize (especially if your phone is in dark mode), here’s a direct link to the list.

The Ranking

The Logic Behind the Rankings

Since we’re trying to map out a lot of things that we don’t know, let’s start with the one thing we do know: the NBA is the best league in the world.

But how do we know that? We can’t prove it on the court, since NBA teams rarely play international teams outside of the occasional preseason game.

In my opinion, one simple fact proves the NBA’s status: the best players from every other league in the world—whether that’s college, the G League, or overseas professional leagues—end up in the NBA, if the league wants them.

Here, we’re looking at the average productivity of NBA players who appeared in other competitions the year prior, expressed in percentiles. In general, these are players who ranked among the top performers in their respective leagues.

There’s also one more thing we do know: in countries with multiple tiers, a first-tier league is always better than a second-tier league, and so on.

If we take Spain as an example and examine player movement between leagues over the past five years, we see exactly what we’d expect. On average, the best players from the second tier move up to the ACB, while the best players from the third tier move up to the second tier. Meanwhile, the weakest performers from the top tier drop down to the second tier, and so on.

Players, like workers in any industry, seek better salaries and conditions. Employers, in turn, seek the best available talent.

This study, then, is based on a core assumption: if League A consistently acquires the best-performing players from League B, and, in turn, League B acquires the worst-performing players from League A, then League A is a better level of competition than League B.

If we apply that logic to every movement between leagues and calculate the productivity differentials between incoming and outgoing players, we should arrive at an approximate quality gap between leagues themselves.

With the logic now established, and after organizing, matching, and cleaning up data from over 250,000 individual season stat lines sourced from RealGM, we need to define the whats and the hows: which metric we’ll use to define productivity, and how we’ll utilize those productivity differentials to rank each league.

The Process (I): What to Rank

I’d love to have some of the most respected catch-all stats available for every league and competition. Unfortunately, those metrics are publicly available only for the NBA, and building most of them from scratch would require play-by-play data that we don’t have access to. In the absence of BPMs, RAPMs, and LEBRONs, we’ll have to work with metrics that are based entirely on box-score data.

Among those, we’ll use the highest-ranked metric from Bryan Kalbrosky’s 2021 survey on advanced stats: FIC/40. It’s far from a perfect metric and should be viewed for what it is: an indicator of overall box-score productivity normalized by playing time, not a definitive measure of efficiency or impact on winning.

With that out of the way, the method itself is fairly simple. We compare the average FIC/40 of players moving between two leagues and calculate the differential between incoming and outgoing players. If the quality (as measured by FIC/40) of players going from League B to League A is higher than the quality of players moving in the opposite direction, then League A is a higher level of competition.

Here’s what that looks like:

The Process (II): How to Rank

Now that we have every matchup, it’s time to rank every league. With over 150 competitions and roughly 6,000 league-to-league matchups, things won’t be perfectly ordered. The best league in the world won’t go 149–0 against the field, the second-best league won’t go 148–1, and so on. That’s simply not how the real world works. There are also gaps in the data, as not all leagues exchange players with one another.

I thought about other systems that rank large numbers of teams that don’t necessarily play each other. My mind went to college sports, and specifically to SRS. As explained by Sports Reference, SRS is a ranking that takes into account not only the win/loss record, but also the strength of schedule and margin of victory.

We can treat player movement between leagues like a game. If a league has a positive differential between incoming and outgoing player quality, that’s a win. The size of the differential becomes the margin of victory.

Using those results, we can build an SRS-style ranking for basketball leagues across the entire world. For this study, I used a slightly modified version of John Frederick King’s SRS script for R.

Sanity Checks, Subjective Takeaways, and Potential Future Additions

With the rankings complete, how do we know if the results make sense? Subjectively, the top of the list looks exactly as you’d expect: the NBA at the top, followed by a mix of well-known international competitions such as the Olympics, EuroLeague, EuroBasket, the FIBA World Cup, and the Spanish ACB.

There’s also objective validation. Returning to the Spain example detailed above, leagues with multiple tiers should appear in the rankings in the same hierarchical order they have in real life — and that’s exactly what happens here.

Subjectively, a few things stand out.

Lower-level French competitions appear somewhat overrated. It’s difficult for me to justify France’s second division being equivalent to Lithuania’s top flight, or its third division being comparable to conferences like the Atlantic-10 or the Mountain West.

That said, France has been one of the world’s most prolific exporters of young basketball talent over the past five years, which helps explain why its leagues perform so well in a metric that favors countries with a positive trade balance of talent.

I also believe that some NCAA D-I conferences are slightly underrated, though not dramatically so. Vashro noted that lower-tier D-I conferences were comparable to lower European competitions like Luxembourg’s Total League, while the top NCAA conferences were equivalent to high-level domestic competitions in Europe, such as the first divisions in Turkey, France, and Germany.

In this study, top conferences still sit alongside elite European competitions, but the lower conferences are closer to youth competitions such as the U16 EuroBasket, U18 AfroBasket, and U18 EuroBasket Division B.

I do think that the transfer portal has gutted the teams in lower conferences, so a lower ranking than they had in 2015 makes sense. However, these rankings are also a byproduct of studying talent movement between leagues: only the top players in lower conferences tend to move on to the professional ranks, while the top players in the pros or youth competitions rarely move into those lower D1 conferences. This creates a negative trade balance of basketball talent, which is precisely what this study measures.

If I ever get the chance to update this study, I plan to introduce age as a variable. Rather than relying on raw production, I’ll use a metric of production relative to expected output by age, as player movement around the world is not tied exclusively to productivity but also to perceived potential, an aspect in which age plays a critical role.

Another potential reference point would be average productivity changes for players who appear in two different leagues. If players consistently perform better in League B than in League A, then League A should represent a higher level of competition. However, age would again need to be included as a variable to separate the true effect of competition level on performance from the effect of natural development or age-related decline.

Usage

The goal of this study was not to build a translation model, but to provide a quick reference point for fans, basketball decision-makers in the college and international game, and frankly, myself, about comparable levels of competition. The next time you’re watching or scouting a player who made a statistical impact in a league you’re unfamiliar with, this list can help contextualize that production.

There are thousands of basketball competitions in the world, and it’s impossible to fully understand every one of them without years, if not decades, of watching and scouting experience. If this titanic task of ranking every league with sufficient available data helps people break through the international iceberg, even just a little, then the study has done its job.

This is awesome man

Very cool…could definitely be useful for international draft models I would think?

Also, I expect the CEBL to move up these rankings over the next few years…so many good G League guys coming over and it’s getting more traction with quality players overseas too.